|

At the 2007 Gesneriad Society convention in Miami,

two plants of this species were exhibited, both having traveled 3000

miles to get there!

Bill Price's plant

is shown on the Gesneriad Society website.

Peter Shalit's was equally striking, with fewer flowers but two large leaves,

which makes the transportation accomplishment all the more impressive.

Bill's striking tuber-and-flowers plant brought up an interesting judging

puzzle: How do you judge "cultural perfection" if there aren't any leaves?

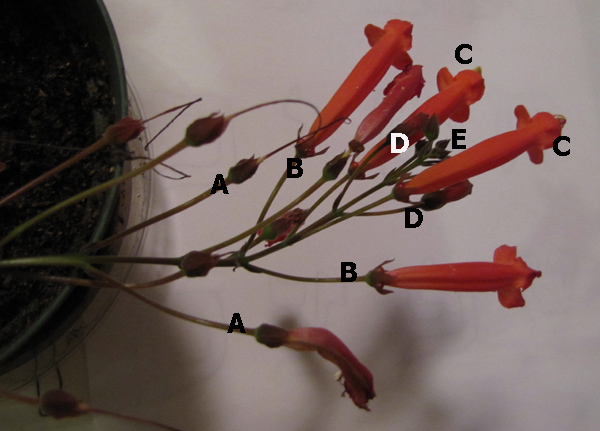

The picture below is Peter's plant.

In 2010, Bill Price exhibited a sinningia collection which included a large

Sinningia defoliata with five leaves.

Pictures of this plant can be seen

here.

Feature table for Sinningia defoliata

Plant Description

|

| Growth |

Determinate, sort of |

| Habit |

Extremely compressed stem(s), with only one leaf per stem expanding.

Flowerstalks grow directly from tuber |

| Leaves |

Light green. Upper surface slightly sticky. |

| Dormancy |

Leaves deciduous, with compressed-stem stumps

remaining on tuber.

Dormancy may be very short -- sometimes blooming lasts until

new leaf growth begins.

On the other hand, dormancy under my conditions has lasted

as long as six months (but not recently -- new shoots starting

before the bloom cycle is complete is the usual situation).

|

Flowering

|

| Season |

According to Appendix 1 in Perret et al.

[see references]

S. defoliata blooms in August-October in Brazil.

This is late winter and early spring there.

Mine usually blooms in autumn or winter.

The plants exhibited by Bill Price and Peter Shalit in Miami 2007 were

obviously blooming in mid-summer.

Growing under lights may disrupt the normal blooming schedule.

My plants (whether indoors or outdoors) sometimes don't come out

of dormancy until summer solstice (mid-June) -- but see

above. |

| Flower |

Tubular, red |

Horticultural aspects

|

| Hardiness |

A plant I put outdoors survived 28 F [-2 C] without damage, not even to the

leaves. However, the plant did not bloom, even though it had done

so in previous years. |

| Propagation |

From seed is easiest, but

propagation by cuttings has been done. |

| Problems and pests |

Mildew on one plant out of three, one year |

| Recommended? |

Highly!

A single leaf appearing to grow directly from the tuber

is a great conversation piece, even when the plant is not

in bloom.

When it is in bloom, it's even more interesting!

More people should grow this species.

The only downside is that the horizontal leaf takes up a lot of

room under lights.

Positioning the plant in front of a window, so that the

light comes from the side, can result in a vertical leaf,

which is very striking. |

Botany

|

| Taxonomic group |

The second core group

of the Corytholoma clade. |

|

Mauro Peixoto's web site has what appears to be a picture of

S.defoliata in habitat.

|

Malme, 1937, as Corytholoma defoliatum.

Chautems transferred it to Sinningia in 1990.

Etymology: from Latin de- ("off, down, away") +

-folia ("leaf").

Not, presumably, "leafless" but rather "leaf dropper".

While most sinningias drop their leaves at some point,

it is the habit of blooming while leafless that inspired the name.

|